Bleak House Working Notes

Editor: Adam Grener

Critical Introduction

How to cite:

Critical Introduction (MLA): Grener, Adam. “Bleak House Working Notes: Critical Introduction.” Digital Dickens Notes Project. Anna Gibson and Adam Grener, dirs. 2022. Web. http://dickensnotes.com/notes/bleak-house/

The Working Note transcriptions for Bleak House (MLA): Dickens, Charles. “Bleak House Working Notes,” transcribed and edited by Adam Grener and Isabel Parker. Digital Dickens Notes Project. Anna Gibson and Adam Grener, dirs. 2022. Web. http://dickensnotes.com/notes/bleak-house/mirador/

Individual editorial annotations are written by Adam Grener and can be cited by annotation number as displayed at the beginning of an annotation (e.g. BH.II.L2).

The Compositional Context of Bleak House

Dickens began composition of Bleak House in late 1851, but the first hints of the novel date back to February when he mentions to Mary Boyle “the first shadows of a new story hovering in a ghostly way about me (as they usually begin to do, when I have finished an old one)” (Letters 6.298). By October, Dickens was discussing advertisements for the new novel with his publishers Bradbury & Evans, though no notice appeared until February 14, 1852, just two weeks before the first installment was published (Slater 337). But on December 7, 1851, Dickens informed Evans that he had “only the last short chapter to do, to complete No. I” (this chapter eventually became chapter 2; see BH.I.R1) (Letters 6.550).

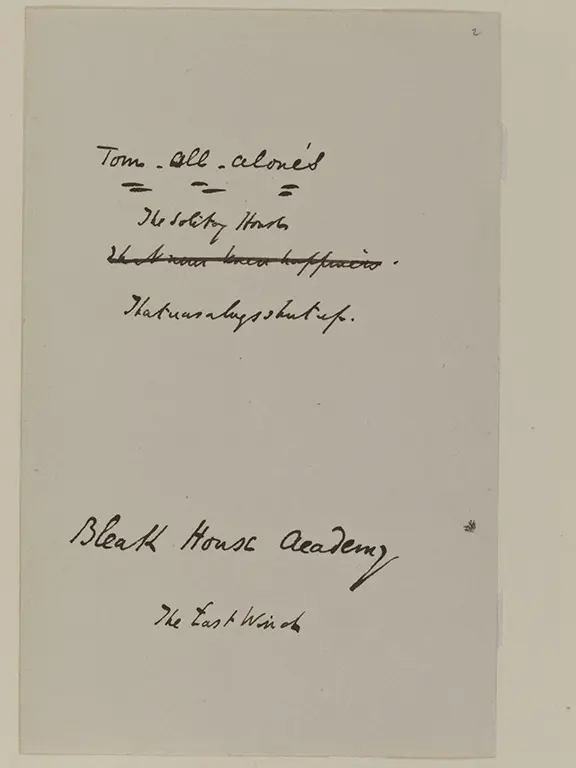

As with his previous novel David Copperfield (1849-50)—as well as the earlier Martin Chuzzlewit (1843-44)—Dickens retained a series of sheets on which he tested different titles for the novel, sheets which are now bound with the manuscript and Working Notes for the novel. All but one of these sheets features “Tom-all-Alone’s” as part of a possible title. This is usually accompanied by “The Ruined House” or “The Solitary House,” with “Building,” “Factory,” and “Mill” also appearing as alternatives. The central theme of Chancery also appears in most iterations, usually as “The Ruined House / That got into Chancery / And never got out.” Although the order of these sheets is uncertain, in Harry Stone’s speculative sequencing, the idea of the “East Wind” appears late in the process, before Dickens settled on “Bleak House and the East Wind” (Stone Working 185). This title appears on the headers of the Working Notes for the first two numbers, before Dickens finally landed on the shortened title Bleak House and amended the heading of the Working Note accordingly in finalizing the first installment. The heading on the Working Note for No. II still reads “Bleak House and the East Wind.”

That Dickens would eventually settle on “House” as part of the title is perhaps not surprising, given that late 1851 found him preoccupied with his move to Tavistock House in Bloomsbury, located a few kilometers north of Chancery Lane and the novel’s famous opening portrait of Holborn Hill. Dickens had secured a lease of the premises in July 1851, but oversaw extensive refurbishments before moving in (the family would live there until 1860). In October, Dickens was “wild to begin a new book” (Letters 6.506), but “the whirling of the story through one’s mind, escorted by workmen” (6.510) proved distracting. As he wrote to Burdett-Coutts on the 8th of October (6.513):

I have no news—except that I am three parts distracted and the fourth part wretched, in the agonies of getting into a new house—Tavistock House, Tavistock Square. Pending which desirable consummation of my troubles, I can not work at my new book—having all my notions of order turned completely topsy-turvy.

While Dickens and his family had settled into Tavistock House by the end of 1851, the period of Bleak House’s composition through to the middle of 1853 involved movement. Dickens made trips to the provincial north with his amateur theatrical troupe to raise funds for the Guild of Literature and Art, which he founded along with Forster, Edward Bulwer Lytton and others in 1851 (see Hack). But Dickens also felt the need to flee London several times to focus on his novel, including trips to Folkestone in July 1852, Brighton in March 1853, and a longer stay in Boulogne, France from June 1853, where he wrote the last four monthly installments of Bleak House. This last trip was preceded by a period of significant illness, where Dickens spent six days “in bed, where [he] underwent great pain and became extremely weak” (Letters 7.95).

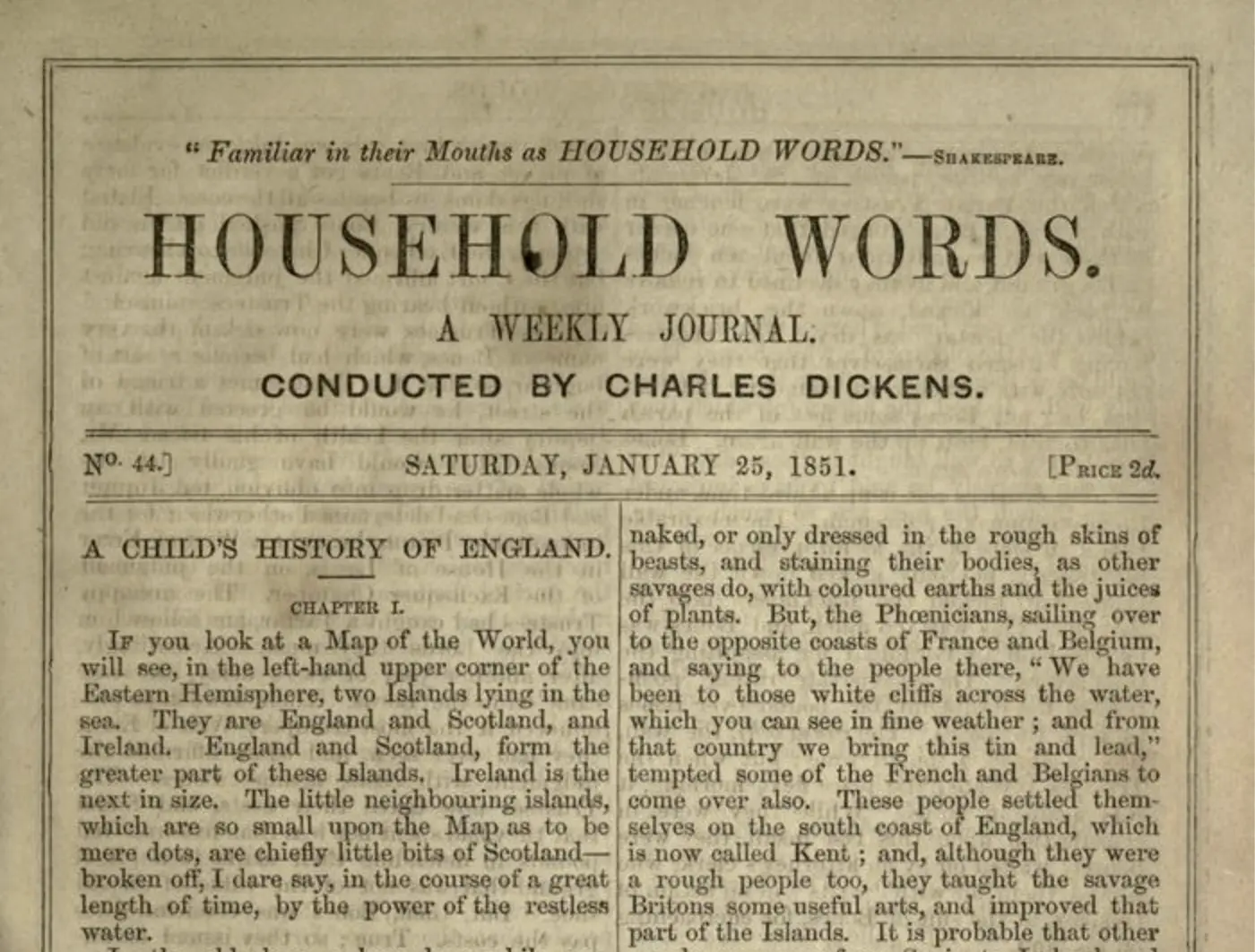

Dickens was under great professional strain through these years. Alongside writing Bleak House, he was running Household Words, which was published weekly; writing A Child’s History of England, whose chapters appeared sporadically in Household Words from January 1851 through December 1853; working closely with Burdett-Coutts on Urania Cottage and other philanthropic projects; and responding to various public engagements and invitations, many of which he declined, citing his commitments to Household Words and Bleak House.

The Critical and Popular Reception of Bleak House

Building on the reputation Dickens had established with David Copperfield, Bleak House was a great popular success during its serial run. Sales for the novel were “markedly greater than that of any of the monthly serials written during the 1840s,” and initiated a sustained increase in sales that would continue through the remainder of his career (Patten 162). Based upon the sales of Copperfield, Bradbury & Evans ordered an initial printing of 25,000 copies of the first installment (168). However, those copies all sold by the end of the first day of March 1852, prompting a further printing of 5,000 copies and then another 2,000 (169). By Numbers IV and V, initial printings were up to 35,000 copies, and they remained at 34,000 through the completion of the novel’s serial publication. As Dickens wrote to Lavinia Watson upon completing the novel in August 1853: “It has retained its immense circulation from the first; beating dear old Copperfield by a round ten thousand and more. I have never had so many readers” (Letters 7.134).

The immediate critical response to Bleak House was, however, more mixed. As scholars have suggested, the turn in Dickens’s critical reception after mid-century may have followed from his “wide-sweeping criticism of society” that “alienated liberal and conservative alike” (Patten 162). Regardless, initial reviews of Bleak House found merit in passages and parts of the novel, with Inspector Bucket and Jo drawing particular praise. On the whole, though, reviewers found the novel lacking in coherence and plot. An unsigned review in the Illustrated London News (24 September 1853) claimed that “Mr Dickens fails in the construction of a plot” (Collins 281). Similarly, George Brimley, in an unsigned review in the Spectator (24 September 1853), wrote that the novel was “chargeable with not simply faults, but absolute want of construction” (283). Many reviewers cited Dickens’s “tendency to disagreeable exaggeration” in the novel’s characters (287) as well as its “entire absence of humour” (288). An unsigned review in Bentley’s Miscellany (October 1853) captures the tension between the novel’s commercial and critical reception: “Everybody reads—everybody admires—everybody is delighted—everybody loves—and yet almost everybody finds something to censure, something to condemn” (Collins 289).

While these assessments generally appeared at the conclusion of the novel’s serial run, elements of the novel also elicited immediate response. One such element was the death of Krook by Spontaneous Combustion at the novel’s mid-point in Number X. In particular, George Henry Lewes criticized Dickens and his departure from scientific possibility in an article in The Leader on December 11, 1852. Dickens bolstered his defense of the death’s plausibility with a “heavy-handed” (Slater 349) description of the inquest in chapter 33 at the start of the next number (No. XI). This prompted further responses from Lewes in The Leader on the 5th and 12th of February, where he insisted that “the evidence in favour of the notion is worthless; that the theories in explanation are absurd; and that, according to all known chemical and physiological laws, Spontaneous Combustion is an impossibility” (Collins 275). Meanwhile, Dickens had consulted his friend Dr. John Elliotson, responding to him on the 7th of February (Letters 7.22):

I am very truly obliged to you for the loan of your remarkable and learned lecture on Spontaneous Combustion; and I am not a little pleased to find myself fortified by such high authority. Before writing that chapter of Bleak House, I had looked up all the more famous cases you quote (as I dare say you divined in reading the description); but three or four of those you incidentally mention—two of them in 1820—are new to me. And your explanation is so beautifully clear, that I could particularly desire to refer to it several times before I come to the last No. and the Preface.

Dickens then responded at length in private letters to Lewes later in the month, and while he did not revisit the evidence within the novel itself, he did address the issue again—with direct reference to Lewes’s criticism—in the novel’s Preface (written at the end of its serialization) (see P. Denman, Haight).

Dickens’s biting critique of philanthropists such as Mrs. Jellyby, Mrs. Pardiggle, and Miss Wisk was another facet of the novel that provoked public response during its serial run. This reaction was in part generated through comparison with Harriet Beecher Stowe’s abolitionist novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Stowe’s novel appeared serially from June 1851 to April 1852, and was first published in England at the end of April, with advertisements appearing in the third monthly number of Bleak House (May 1852). In particular, during September and October 1852 Lord Thomas Denman published a series of articles in the London Standard that criticized Dickens by reviewing the first seven numbers of Bleak House alongside Stowe’s novel. Denman was Lord Chief Justice of England until 1850, a “tireless worker for legal reform and for abolition” (Stone “Stowe” 190), as well as a good friend of Dickens. In contrast to his exalted praise of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Denman took issue with Dickens’s satirical portrait of Mrs. Jellyby and her “telescopic philanthropy.” “We do not say,” Denman wrote, “that [Dickens] actually defends slavery or the slave-trade; but he takes pains to discourage, by ridicule, the effort now making to put them down” (T. Denman 9). Dickens was taken aback by these criticisms, and in writing to Denman’s daughter Margaret Cropper in December 1852 after Denman had suffered a series of strokes, Dickens praised him as “one of the noblest spirits in the world” but also rebutted his critiques. In regard to Mrs. Jellyby, Dickens wrote that she “gives offence merely because the word ‘Africa’, is unfortunately associated with her wild Hobby. No kind of reference to Slavery is made or intended, in that connexion” (Letters 6.825).

Ultimately, though, Dickens himself appears to have been pleased with his work as the novel’s composition and serial publication came to a conclusion. As he wrote to Lavinia Watson: “I like the conclusion very much and think it very pretty indeed. The story has taken extraordinarily—especially during the last five or six months when its purpose has been gradually working itself out” (Letters 7.134).

The Working Notes for Bleak House

The Working Notes for Bleak House suggest that Dickens began each number dividing it by default into three chapters. For installments that eventually became four chapters (Numbers I, IX, XIII, XIV, XVI), differences in ink and nib indicate that the chapter heading for the fourth chapter was always added to the Note later. This is most explicit in No. IX, where the headings for chapters 26-28 appear in blue ink, and the heading for chapter 29 is added at the bottom in black ink. Read alongside the manuscript and corrected proofs, the Working Notes also indicate that many of the chapter titles were conceived and added at a late stage in the compositional process. Around twenty chapter titles, for example, were added in ink to the type-set proofs, with Dickens usually returning to the manuscript and Working Notes to document those titles. For No. VII, only one chapter title (“A New Lodger,” chapter 20) appears in the manuscript, and this is in black ink where blue ink was used for the entire manuscript for the number. No chapter titles appear in the manuscript for No. XIII (chapter 39-42). One notable exception to this pattern is chapters given the generic title “Esther’s Narrative.” Many of these chapter titles appear to have been written at the same time as the chapter headings on the Working Notes, with Dickens perhaps relying on this generic title to help him structure numbers by deciding early in the compositional process about shifts between the novel’s first- and third-person narration.

While Dickens’s handling of the novel’s two modes of narration was largely an open question as composition proceeded month-by-month, the Working Notes provide plenty of evidence of Dickens’s careful handling and preparation of key elements of the plot. In the first half of the novel’s Working Notes, for example, we see indications of Dickens’s development of minor elements that will nevertheless become important later in the novel. These include the gradual developments in Richard’s character (see Notes for Nos. III, VI, and VIII); the connection between Watt Rouncewell and Lady Dedlock’s maid Rosa that culminates in their marriage late in the novel (see Notes for Nos. II, IV, VI, and IX); and the connections between Skimpole, the debt collector Coavinses, and Coavinses’s daughter Charley, who will become Esther’s maid and the vector for her disfiguring illness (see Notes for Nos. V, VI, VIII, and X). The middle sequence of the novel’s Notes also documents Dickens’s careful management of key developments: the gradual revelation of Esther’s love for Allan Woodcourt (see Note V: “‘I have forgotten to mention—at least, I have not mentioned—’”); the disclosure, through the discoveries of Guppy and Tulkinghorn, that Lady Dedlock is Esther’s mother (see Note for No. VII, where in “Mems: for future” Dickens works out these threads); and Esther’s infection with smallpox in No. X, which threatens to damage both her romantic prospects and her resemblance to Lady Dedlock. As Dickens wrote to Burdett-Coutts in mid-November 1852 (following the completion of the composition of No. X): “I have been so busy, leading up to the great turning idea of the Bleak House story, that I have lived this last week or ten days in a perpetual scald and boil” (Letters 6.805). Yet while H.P. Sucksmith, in the first scholarly analysis of the Working Notes for Bleak House in 1965, highlights the Notes as “evidence of the control which Dickens regarded as one of the triumphs of his growing professionalism” (52), our annotations of these Working Notes also highlight evidence of uncertainty, spontaneity, and contingency in the composition of Bleak House.

Works Cited

- Collins, Philip, ed. Dickens: The Critical Heritage. Routledge and Keagan Paul, 1971.

- Denman, Peter. “Krook’s Death and Dickens’s Authorities.” Dickensian, vol. 82, no. 3, 1980, pp. 131-141.

- Denman, Thomas. Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Bleak House, Slavery and Slave Trade: Seven Articles, 2nd edition, Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1853. The Cornell University Library Digital Collections.

- Dickens, Charles. Bleak House, edited by Nicola Bradbury. Penguin, 1996.

- ——. The Letters of Charles Dickens: The Pilgrim Edition, 12 volumes, edited by Madeline House, Graham Storey, and Kathleen Tillotson, Oxford UP, 1982-2002.

- Hack, Daniel. “Literary Paupers and Professional Authors: The Guild of Literature and Art.” Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, vol. 39, no. 4, 1999, pp. 691-713.

- Haight, Gordon. “Dickens and Lewes on Spontaneous Combustion.” Nineteenth-Century Fiction, vol. 10, no. 1, 1955, pp. 53-63.

- Parker, David. “Dickens, the Inns of Court, and the Inns of Chancery.” Literary London: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Representation of London, vol. 8, no. 1, March 2010. Accessed on 26/10/2022.

- Patten, Robert. Charles Dickens and His Publishers, 2nd ed., Oxford UP, (1978) 2017.

- Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens. Yale UP, 2009.

- Stone, Harry. “Charles Dickens and Harriet Beecher Stowe.” Nineteenth-Century Fiction, vol. 12, no. 3, 1957, pp. 188-202.

- ——. Dickens’ Working Notes for his Novels. University of Chicago Press, 1987.

- Sucksmith, Harvey Peter. “Dickens at Work at Bleak House: A Critical Examination of his Memoranda and Number Plans.” Renaissance and Modern Studies, vol. 9, 1965, pp. 47-85.