Little Dorrit Working Notes

Editor: Anna Gibson

Critical Introduction

How to cite:

Critical Introduction (MLA): Gibson, Anna. “Little Dorrit Working Notes: Critical Introduction.” Digital Dickens Notes Project. Anna Gibson and Adam Grener, dirs. 2023. Web. http://dickensnotes.com/notes/little-dorrit/

The Working Note transcriptions for Little Dorrit (MLA): Dickens, Charles. “Little Dorrit Working Notes,” transcribed and edited by Anna Gibson and Frankie Goodenough. Digital Dickens Notes Project. Anna Gibson and Adam Grener, dirs. 2023. Web. http://dickensnotes.com/notes/little-dorrit/mirador/

Individual editorial annotations are written by Anna Gibson and can be cited by annotation number as displayed at the beginning of an annotation (e.g. LD.IV.R2).

From “Nobody’s Fault” to Little Dorrit

Dickens had immense difficulty getting started on his new monthly novel in the spring and summer of 1855. In January he began jotting down ideas in a new Memoranda book that, given the number of entries later marked “Done in Dorrit,” functions as an extension of the novel’s Working Notes. Despite this early planning, the novel that bore the title “Nobody’s Fault” through composition of the first three numbers (see LD.I) proved difficult to plan and write.

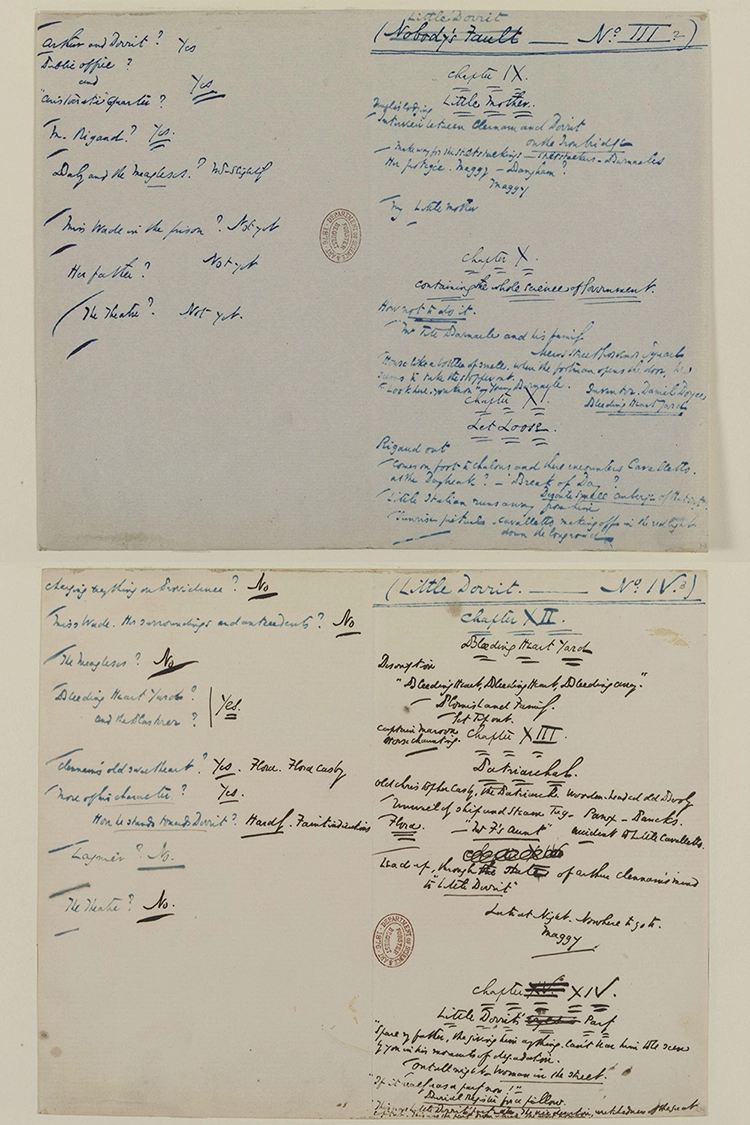

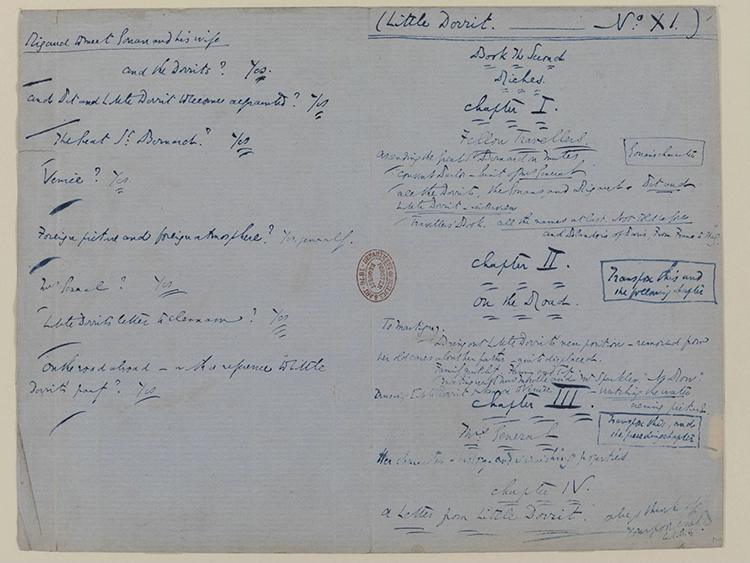

A comparison between the first few Working Notes for Little Dorrit and those for the prior four novels indicates Dickens’s level of uncertainty. His friend John Forster placed a facsimile of the Notes for Nos. I of David Copperfield and Little Dorrit side-by-side in his 1872 biography to illustrate “the labor and pains” of the Little Dorrit Notes in comparison with the “lightness and confidence of handling” of those for Copperfield (2.182). An even starker comparison can be made to the sparse early Notes for Bleak House, Dickens’s most recent monthly novel. The density of the Little Dorrit Notes indicates just how heavily he relied on these pages to manage and work through—to “accept and reject”—his “ideas” (Letters 8.33).

The plethora of heterogeneous ideas Dickens generated for this novel explains his difficulty getting started. On May 8, 1855 he wrote to Angela Burdett-Coutts, complaining of a “state of restlessness impossible to be described—impossible to be imagined—wearing and tearing to be experienced. I sit down of a morning, with all kinds of notes for my new book” (Letters 7.613). His letters from the period repeatedly reiterate this same “restlessness.” By May 24, he would report to Burdett-Coutts that his “condition of restlessness is not improved. All the symptoms are very bad. The only new feature is, that I am actually at work and in the middle of No. One” (7.629). The first installment would be published on November 30, 1855 and would become an immediate bestseller, with 38,000 copies sold within a month (Slater 402). While his “wretchedness” (Letters 8.60) would subside as Dickens reached Nos. VII-X, the novel remained difficult to manage; he still found his “knitted brows… turning to cordage over Little Dorrit” as late as his work on No. XVI in January 1857 (8.270).

Forster claims that the novel’s original title was tied to Dickens’s plan for “a leading man for a story who should bring about all the mischief in it, lay it all on Providence, and say at every fresh calamity, ‘Well, it’s a mercy, however, nobody was to blame you know!’” (Forster 2.179). A note pertaining to this idea first appears in Dickens’s Memoranda book (6) and features twice in the Working Notes, first for No. II (“The man who comfortably charges everything on Providence? Not yet,” see LD.II.L3) and again in No. IV (see LD.IV.L1). As Harvey Peter Sucksmith points out in his introduction to the comprehensive Clarendon edition of the novel, Dickens soon realized that “the notion of one man’s responsibility for all the mischief in the story clashed with his awareness that the condition of England must be blamed on a whole social, economic, and political scheme of things” (xx-xxi). Indeed, John Butt and Kathleen Tillotson are skeptical that Dickens ever intended for such a leading protagonist to encompass the critique implied by the original title (224). Dickens’s letters from this period repeatedly condemn the “failure” of representative government, especially in light of what he perceived as a mishandling of the Crimean War (Letters 7.713). He joined the Administrative Reform Association in June of 1855 and voiced his frustration at political mismanagement of the country in a number of Household Words articles throughout the novel’s conception and composition.1

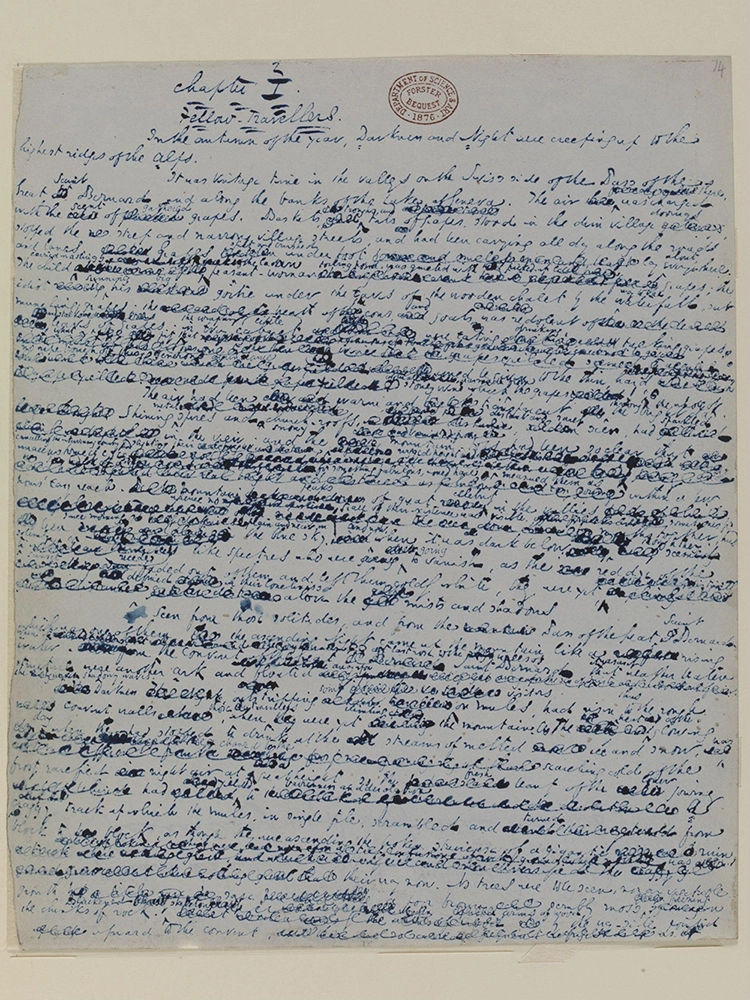

It was as he wrote No. III, with the creation of the Circumlocution Office to anchor his critique of political incompetence, that Dickens translated his original idea for a single protagonist abdicating responsibility into a systemic critique of bureaucratic inadequacy. “There is a dash in No. 3,” he wrote to his friend Frank Stone, “at the great system of abuse under which we live” (Letters 8.36). Having “blow[n] off a little… indignant steam” in No. III (Letters 7.716), Dickens was able to turn his attention to the character of Little Dorrit, whose name had been merely “Dorrit” in the early Notes and manuscript (see LD.III.R2): “I can make Dorrit very strong in the story, I hope,” he wrote to Forster (8.182). He also magnified the prison motif he had introduced in his opening chapters as a metaphor for the ills of society and the obstacles to individual action.

Free from its ties to a single character, the lack of agency implied by Dickens’s original title became a central strategy for the novel. That strategy had its origins in a new idea Dickens contemplated as he composed the early numbers. He wrote to Forster that he “had half a mind to begin again” (Forster 2.182):

It struck me that it would be a new thing to show people coming together, in a chance way, as fellow-travellers, and being in the same place, ignorant of one another, as happens in life; and to connect them afterwards, and to make the waiting for that connection a part of the interest.

An extensive entry in the Note for No. I prefigures the language of this letter, indicating that Dickens was likely already considering this idea as he worked on the opening installment (see LD.I.L6 for analysis of this note.):

People to meet and part as travellers do, and the future connexion between them in the story, not to be shewn to the reader but to be worked out as in life. Try this uncertainty and this not-putting of them together, as a new means of interest. Indicate and carry through this intention.

While Dickens did not “begin again,” he did integrate these ideas of uncertain fate, travelers meeting, networked interconnection, and destined interactions throughout the novel, both with echoes of this language in its content (see, for instance, Book I chapters 2, 9, and 15) and via the complex intertwining of multiple narrative threads. The lack of agency Dickens had originally attached to his title and leading character became something of a formal strategy for a complex novel of interconnections, some of which remained unclear even to the author quite late in his composition (see, for instance his “Mems for working the story round”). Indeed, what the Notes help us read as a carefully considered aspect of the novel’s construction has often been read by critics as its most significant fault.

”Destitute of a Well-Considered Plot”: Drawing from Life

While early reviews of the novel were enthusiastic, they became increasingly hostile as it neared completion (Slater 402, 427).2 A March 1857 Fraser’s Magazine article named it “decidedly the worst” of Dickens’s novels, its author having “no conception of a well-constructed plot” (Forsyth 261-62); the following month’s Blackwood’s similarly deemed it “destitute of a well-considered plot” (Hamley 502).

Among the critiques was a common accusation of the novel’s excessive topicality: “All his inspiration seems to come from without” wrote one reviewer (Hamley 495). Indeed, despite being set “thirty years ago” (LD 1), the novel draws frequently on current issues and events, from Sunday trading (see LD.I.R16) to patent law (see LD.III.R12). As Butt and Tillotson point out, in his critique of governmental inadequacy, Dickens was “catching up a current notion” in response to mismanagement of the Crimean War: “‘Who’s to Blame?’ was the question everyone was asking… and the answer was ‘Nobody’” (229).

In some cases, Dickens was open about his incorporation of current events. He references “a Russian war, and… a Court of Inquiry at Chelsea” in his preface (LD lix). He also admits there that his “extravagant conception” of Mr. Merdle “originated after the Railroad-share epoch, in the times of a certain Irish bank,” a reference to the 1856 suicide of the infamous Irish politician and financier John Sadlier after the failure of his speculations (see LD.VI.R17).

Dickens also incorporated his own life experiences in Little Dorrit. The novel’s cosmopolitan plot took inspiration from his 1853 excursions to Italy, France, and Switzerland, as well as his 1840s travels recorded in Pictures from Italy (for more, see LD.XI). Michael Slater notes that Dickens’s writings from 1854-55 “show that his imagination was much engaged with his early life” (385), upon which he would draw heavily for his descriptions of the Marshalsea Debtor’s Prison, where his father was incarcerated for three months in 1824 (see LD.II.R7). Dickens had described this period of his life in an autobiographical “fragment” included in the second chapter of Forster’s biography. He drew on it heavily for David Copperfield (see our Critical Introduction for more), but this novel would enable Dickens to return to these difficult memories with greater narrative distance than the first-person mode of Copperfield allowed.

Perhaps a catalyst for Dickens’s memories of his early life at this period was his renewed correspondence in February of 1855 with his first love, Maria Beadnell (now Maria Winter). These long, emotionally charged letters were intensified (perhaps even initiated) by increased strains in Dickens’s own marriage (see Slater 382). In Flora Casby, Dickens would loosely fictionalize his own experience of meeting his “old sweetheart” after more than two decades (see LD.IV.L5). In Slater’s words, he “found himself confronted with a stout woman of forty-four. She had warned him that she was ‘toothless, fat, old, and ugly’ but he had simply brushed this aside. Now, after meeting her again in the flesh he wrote to her in a very different tone” (Slater 388; Letters 7.548).

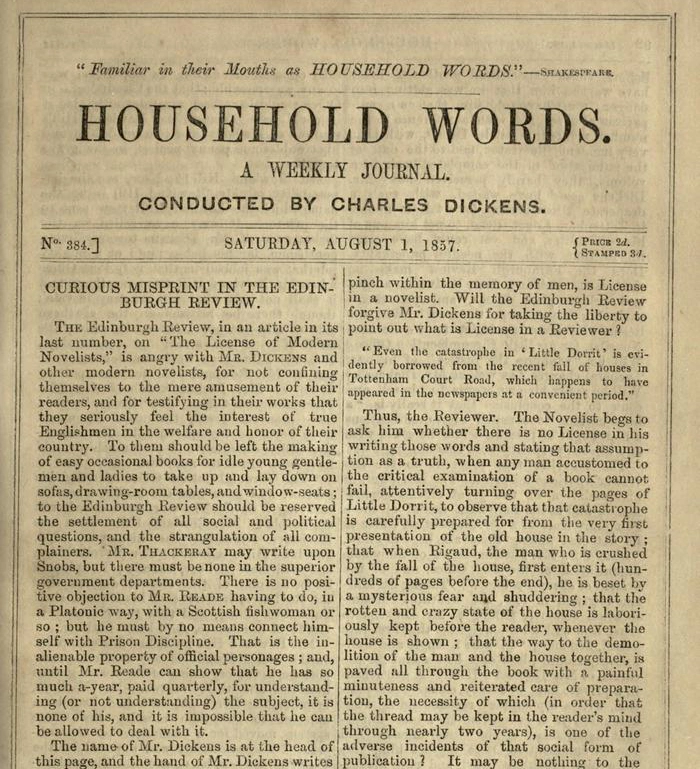

While Dickens drew on his own life and embraced the novel’s topicality in his preface, he took exception when accusations that he was drawing from life challenged his careful control of the narrative. In July 1857, shortly after the novel finished its serial run, an Edinburgh Review article by James Fitzjames Stephen accused Dickens of, among other things, following “popular cries of the day” by basing the collapse of Mrs. Clennam’s house on the recent collapse of three houses on Tottenham Court Road (127). Dickens’s anger at this accusation was such that he mounted his own defense in a Household Words article (“Curious Misprint in the Edinburgh Review”) that denied any such use of this accident, which took place after he had composed the chapter (for more, see LD.XIX-XX.R10). At issue for Dickens was a defense of his careful plotting (97):

[A]ny man accustomed to the critical examination of a book cannot fail, attentively turning over the pages of Little Dorrit, to observe that that catastrophe is carefully prepared for from the very first presentation of the old house in the story […] that the way to the demolition of the man [Rigaud] and the house together, is paved all through the book with a painful minuteness and reiterated care of preparation, the necessity of which (in order that the thread may be kept in the reader’s mind through nearly two years), is one of the adverse incidents of that social form of publication.

The Working Notes back up Dickens’s points here. They include frequent references, as early as No. V, to preparation for the “Rigaud catastrophe” (see LD.V.R3; also LD.I.R17 and LD.XVII.R3).

But Dickens defends more than his management of one plot “thread” here; using the metaphor of paving that appears throughout the Working Notes, he emphasizes his “care of preparation” in the face of Stephen’s accusation that “the plot is singularly cumbrous and confused” (126). Stephen was not alone in identifying this formal fault in Little Dorrit, a “failure of plot” (Brattin) that has continued to interest more recent critics (see, for instance, Carlile, Duckworth, Stewart, and Brattin). A disappointed reviewer in the Leader complained that “the woof of the entire story does not hold together with sufficient closeness, a fault perhaps inseparable from the mode of publication” (Collins 374). Even Forster, Dickens’s staunchest supporter, would later describe “the defect” of Little Dorrit as a “want of ease and coherence among the figures of the story, and of a central interest in the plan of it” (Forster 2.184; see LD.XVI.L7).

Dickens’s defensiveness here, as in his prefaces (see our Scholarly Introduction), about his careful attention to formal preparation makes sense in light of the painstaking planning that his dense Working Notes reveal. More than any previous Notes, those for Little Dorrit are filled with imperative verbal phrases (e.g., pave the way, make way for, pursue, work distantly up to, carry on, work through) that we can read as both instructions to himself and descriptions of the narrative work of a number. In his 1966 overview of these Notes, Paul D. Herring describes “the elaborate memoranda and chapter summaries” not as “indications of what Forster felt was a gradual failing in inventive powers, [but] instead [as] evidence that Dickens was fully aware of the immense task he had set for himself: to present in the world of the novel the ‘prevailing political and social vices’ of the 1850s. How he could best do this is a question most often raised in the number plans” (22).

Mems for Working the Story Round

Much of the criticism about plotting in this novel centers on Dickens’s handling of the Mrs. Clennam mystery plot. Indeed, the Notes shed light on Dickens’s uncertainty about his management of this storyline, which Joel Brattin argues was far from the author’s central interest in this novel (114). He only added the final chapter of No. I, “Mrs Flintwinch has a dream,” after composing No. II, and was uncertain as to its integration as late as his composition of No. IV (see LD.I.R24). He found himself needing an unusual two additional pages of “Mems for working the story round” before he could embark upon the final double number (LD_WN_Mems1; LD_WN_Mems2). These two pages of Mems, in which he collects previous references to Mrs. Clennam’s mystery and Affery’s dreams, show an author both determined to “run the two ends of the book together” (see LD.XVI.R17) and uncertain about how to do so. His “Prospective” mems show Dickens in the process of working through the connections between the Dorrits and the Clennams and the precise details of his mystery plot, details that would still need further refinement in composition (see LD.XIX-XX.R1).

These two pages of Mems offer explicit evidence of how DIckens used his Working Notes for both prospective planning and retrospective summary. Dividing each page in two, he heads each left side “Retrospective” and each right side “Prospective.” While it was his standard practice to record forward-looking generative memoranda and questions on the left, and more detailed chapter notes on the right, no such clear page-division between prospective and retrospective practice takes place in the Working Notes for individual installments. Instead, the temporal layers are often complex and difficult to pinpoint. In some instances, the temporality is clear, as when he combines blue and black-brown inks (No. IV), or when he divides one chapter in two before writing the right-hand Notes for No. XV, but he divides a chapter after writing the right-hand Notes for No. XVI. While certain Notes are predominantly proactive (e.g., Nos. VII, X, XII) and some predominantly retroactive (e.g., No. XV), most suggest a mixture of the two. Indeed, we see many striking examples of concurrent use of both Notes and manuscript, indicating that Dickens moved back and forth between the Notes and the manuscript during composition of this novel (see especially Nos. I-IV and No. VII).

The Little Dorrit Working Notes offer striking evidence of Dickens’s attempts to “work[…] out as in life” the connections between his characters (see, for example, LD.XI.L1, LD.XII.L5, LD.Mems1.R4); to manage his complex mystery plot (see LD.I.R24, LD.IX.R2, LD.Mems1); to work in narrative threads (e.g., LD.XVI.R13); to prepare for future events and anticipate the “future connexion” between characters in a series of parallel chapters and scenes (see LD.V.R3, LD.IX.R16, LD.XII.L2); to return to prior motifs (see LD.V.R12, LD.XII.R5, LD.XVI.R17); and to consider what should, and should not, be “shewn to the reader” (see LD.XI.R6).

Complex and detailed, these Working Notes are filled with insights into Dickens’s compositional practice. As Marcus Stone points out, Dickens’s “effort to imbue every chink and interstice of his design with a carefully planned, slowly emerging purpose is everywhere apparent” (268). And yet the Notes reveal something more interesting than careful control. Mark M. Hennelly suggests that they show him “stag[ing] a stichomythic guessing game with himself over possible solutions to and arrangements of several… narrative puzzles” (194). Alistair Duckworth finds in them some “evidence of continual improvisation,” a push and pull between structural coherence and “skillful bricolage” (115). We might say that Dickens uses the Notes to balance careful authorial control with an attempt to embody the lack of a central controlling agency that is both pivotal to his social critique and the subject of the “intention” he set out for himself in the Note for No. I: to “work… out as in life” the “uncertainty” of “connexion[s] between” people. Read this way, memoranda expressing narrative intention—”Indicate and carry through this intention” (No. I), “Observe this always” (No. X), “Lead, very carefully, on” (No. XII); “Delicately trace out…” (No. XIV)—appear less as decisive instructions and more as efforts to maintain control over an unwieldy narrative with an agency of its own.

Works Cited

- Anderson, Amanda. The Powers of Distance: Cosmopolitanism and the Cultivation of Detachment. Princeton UP, 2018.

- Black, Barbara. “A Sisterhood of Rage and Beauty: Dickens’ Rosa Dartle, Miss Wade, and Madame Defarge.” Dickens Studies Annual, vol. 26, 1998, pp. 91–106.

- Brattin, Joel J. “The Failure of Plot in Little Dorrit.” The Dickensian, vol. 101, no. 466, 2005, pp. 111-115.

- Butt, John, and Kathleen Tillotson. Dickens at Work. Methuen, (1957) 1968.

- Carlisle, Janice M. “Little Dorrit: Necessary Fictions.” Studies in the Novel, vol. 7, no. 2, 1975, pp. 195-214.

- Collins, Philip, ed. Dickens: The Critical Heritage. London: Routledge and Keagan Paul, 1971.

- Dickens, Charles. “A Christmas Carol.” A Christmas Carol and Other Christmas Writings, edited by Michael Slater. Penguin, 2003, pp. 27-118.

- ——. “Curious Misprint in the Edinburgh Review.” Household Words, vol. 16, no. 384, August 1 1857, pp. 97-100.

- ——. “The Demeanor of Murderers.” Household Words, vol. 13, no. 325, 14 June 1856, pp. 505-507.

- ——. The Letters of Charles Dickens: The Pilgrim Edition, 12 volumes, edited by Madeline House, Graham Storey, and Kathleen Tillotson, Oxford UP, 1982-2002.

- ——. Little Dorrit, edited by Harvey Peter Sucksmith. The Clarendon Dickens, Oxford UP, 1979.

- ——. Little Dorrit, Chapters XLIV-XLVII. Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, vol. 14, no. 80, January 1857, pp. 243-261.

- ——. Memoranda. Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1855-1870.

- ——. Our Mutual Friend, edited by Michael Cotsell. Oxford UP, 1998.

- ——. Pictures from Italy, edited by Kate Flint. Penguin. 1998.

- ——. ”A Poor Man’s Tale of a Patent.” Household Words, vol. 2, no. 30, 19 October 1850, pp. 73-75.

- ——. “Prince Bull: A Fairy Tale.” Household Words, vol. 11, no. 256, 17 February 1855, pp. 49-51.

- ——. “A Walk in the Workhouse.” Household Words, vol. 1, no. 9, 25 May 1850, pp. 205-207.

- [Dodd, George.] “A Room Near Chancery Lane.” Household Words, vol. 15, no. 361, 21 February 1857, pp. 190-192.

- Duckworth, Alistair M. “Little Dorrit and the Question of Closure.” Nineteenth-Century Fiction, vol. 33, no. 1, 1978, pp. 110-130.

- Forster, John. The Life of Charles Dickens, 2 volumes. JM Dent & Sons, (1872) 1927.

- [Forsyth, William.] “Literary Style.” Fraser’s Magazine, v. 55, no. 327, March 1857, pp. 249-264.

- [Hamley, E. B.] “Remonstrance with Dickens.” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, vol. 81, no. 498, April 1857, pp. 490-508.

- Hennelly, Mark M. Jr. “The games of the prison children’ in Dickens’s Little Dorrit.” Nineteenth-Century Contexts, vol. 20, no. 2, 1997, pp 187-213.

- Herring, Paul D. “Dickens’ Monthly Number Plans for Little Dorrit.” Modern Philology, vol. 64, 1966, pp. 22-63.

- Kaplan, Fred. Charles Dickens’ Book of Memoranda. The New York Public Library, 1981.

- Milsom, Alexandra. “John Chetwode Eustace, Radical Catholicism, and the Travel Guidebook: The Classical Tour (1813) and Its Legacy.” Studies in Romanticism, vol. 57 no. 2, 2018, p. 219-241.

- Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens. Yale UP, 2009.

- [Stephen, James Fitzjames]. “License of Modern Novelists.” The Edinburgh Review, vol. 106, July 1857, pp. 124-156.

- Stewart, Garrett. “Dickens and the Narratography of Closure.” Critical Inquiry, vol. 34, no. 3, 2008, pp. 393-631.

- Stone, Harry. Dickens’ Working Notes for his Novels. University of Chicago Press, 1987.

- Sucksmith, Harvey Peter. “Introduction.” Little Dorrit, The Clarendon Dickens, Oxford UP, 1979, pp. xiii-xlix.

Footnotes

-

Examples include “Prince Bull: A Fairy Tale” (February 1855); “That Other Public” (March 1855); “The Thousand and One Humbugs” (April 1855), “The Toady Tree” (May 1855); “Cheap Patriotism” (June 1855); and “Nobody, Somebody and Everybody” (August 1856), this last example echoing the novel’s original title. For more on Dickens’s “political disgust” and its manifestation in Dickens’s other writings of this period, see Butt and Tillotson (225-230). ↩

-

Slater notes that “A detailed study of the novel’s reception has shown that twenty-five out of thirty-six traced reviews or notices of the complete, or nearly complete, novel were hostile, using such opprobrious terms as ‘unartistic,’ ‘unnatural’ and ‘uninteresting’” (427). ↩